Great explanations so far!

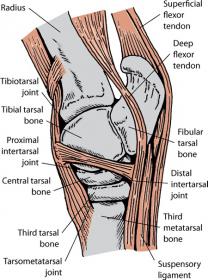

One thing I’d add, OP is that the “fusion” everyone is talking about is in the lower (distal), low-motion joints of the hock. The joint space in there is quite narrow to begin with. You can inject the top, high-motion joints of the hock. But that’s not where you start, and vets usually would prefer not to.

As findeight has described, these big, heavy animals we ask to work create inflammation in the cartilage and synovial lining of their joints. The synovium (tissue) responsible for making that lubricating joint fluid gets irritated and then it makes less-healthy joint fluid… and so inflammation continues…and so the cells in the synovium create worse joint fluid and so on.

That cascade screws things up and one of the main reasons people put chemicals like steroids and/or Hyaluronic Acid into joints. Both help interrupt the inflammatory process. Steroids have some drawbacks as far as their effects on tissue/HA is expensive.

All this is to explain what anyone is doing when they are injecting hocks (typically). And that relates to your question about fusing hocks because people 1) are referring to those narrow, low motion, lower joints of the hock; and 2) injecting those joints if great precisely because you don’t care if they fuse.

As you can imagine, the process of fusing, ruining cartilage until the horse is bone-on-bone but before those bones have knit together, is painful.

And back in the bad old days of yester-century before intra-articular injections were routine, the cure was to bute the horse and ride, ride, ride until that hard work sped up and completed the fusing process.

Anecdotally, I think there’s probably a heritable component to whether or not and when a horse’s hocks fuse. And I think that relates to bone metabolism and irritation-- whether or not the horse with angry soft tissues at the margins of his joints lays down a lot of new bone or does not. That’s because you can see horses with horrific X-rays that are clinically sound or who haven’t worked that hard. And you can see horses who have worked hard with X-rays that are remarkably clean. I suspect that horses in that latter group have some genetics that make them not go crazy with producing new bone… or they have stout, toleration synovial tissue and cartilage. If we can’t genetically engineer horses like that, we should treasure these animals as breeding stock. There’s no other cure of equine osteoarthritis.